A flurry of data and central bank announcements in recent weeks has provided more clarity about where the global economy is heading, reinforcing our view and also highlighting some risks to our outlook.

Three things have become clear. The first is that the global economy is holding up reasonably well, albeit with significant divergences between the performance of individual countries and regions. According to our economic data sources, global GDP expanded by 1.5% quarter over quarter in Q1 2023 compared to -0.4% quarter over quarter in Q4 2022. However, this coincides with China’s abandonment of its zero-COVID policy. Regionally, U.S. GDP slowed to 0.3% quarter over quarter and European growth was broadly stagnant. Despite having experienced a huge hit from higher energy prices, Europe, including the U.K., has so far managed to avoid falling into recession.

"Although the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Canada edged down (driven by energy and food prices), core inflation, primarily driven by wage increases, continues to creep higher."

Second, inflation is proving to be worryingly sticky. Although the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Canada edged down (driven by energy and food prices), core inflation, primarily driven by wage increases, continues to creep higher. At the same time, core CPI in the U.S. increased by another 0.4% month over month. Favourable base effects, as last year’s big monthly increases in energy and food prices drop out of the annual comparison, will bring down year-over-year CPI rates in the coming months. But, the month-on-month increases in prices are still uncomfortably high for central banks and inconsistent with 2% inflation targets.

Lastly, despite the stickiness of inflation, central banks are starting to believe that they may have done enough to bring it down to more acceptable rates later this year. The Bank of Canada hit the pause button in April. The U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 25bps to 5.00-5.25% at its May meeting but signaled that it would likely be the last hike in the cycle. The Bank of England sent a more definitive message when policymakers met in May, but it may also have reached the end of its rate-hiking cycle. While policymakers at the European Central Bank believe they have a bit more work to do, they slowed the pace of tightening from 50bps to 25bps at their most recent meeting.

The Three Questions that Frame Our Outlook

Our outlook for the major advanced economies is framed by three questions.

- How much will the cumulative effect of policy tightening over the past year now cause economic growth to slow?

- What is the extent to which this policy tightening, in turn, causes inflation to moderate?

- Will central banks remain in control of the process, or will they be overwhelmed by a sudden and disorderly tightening of financial conditions caused by problems in the banking system or a shock from elsewhere such as a failure to agree to a deal to lift the federal debt ceiling in the U.S.?

Answers to these questions require judgments that are complicated by the fact that pandemic-related distortions have made this an extremely unusual cycle.

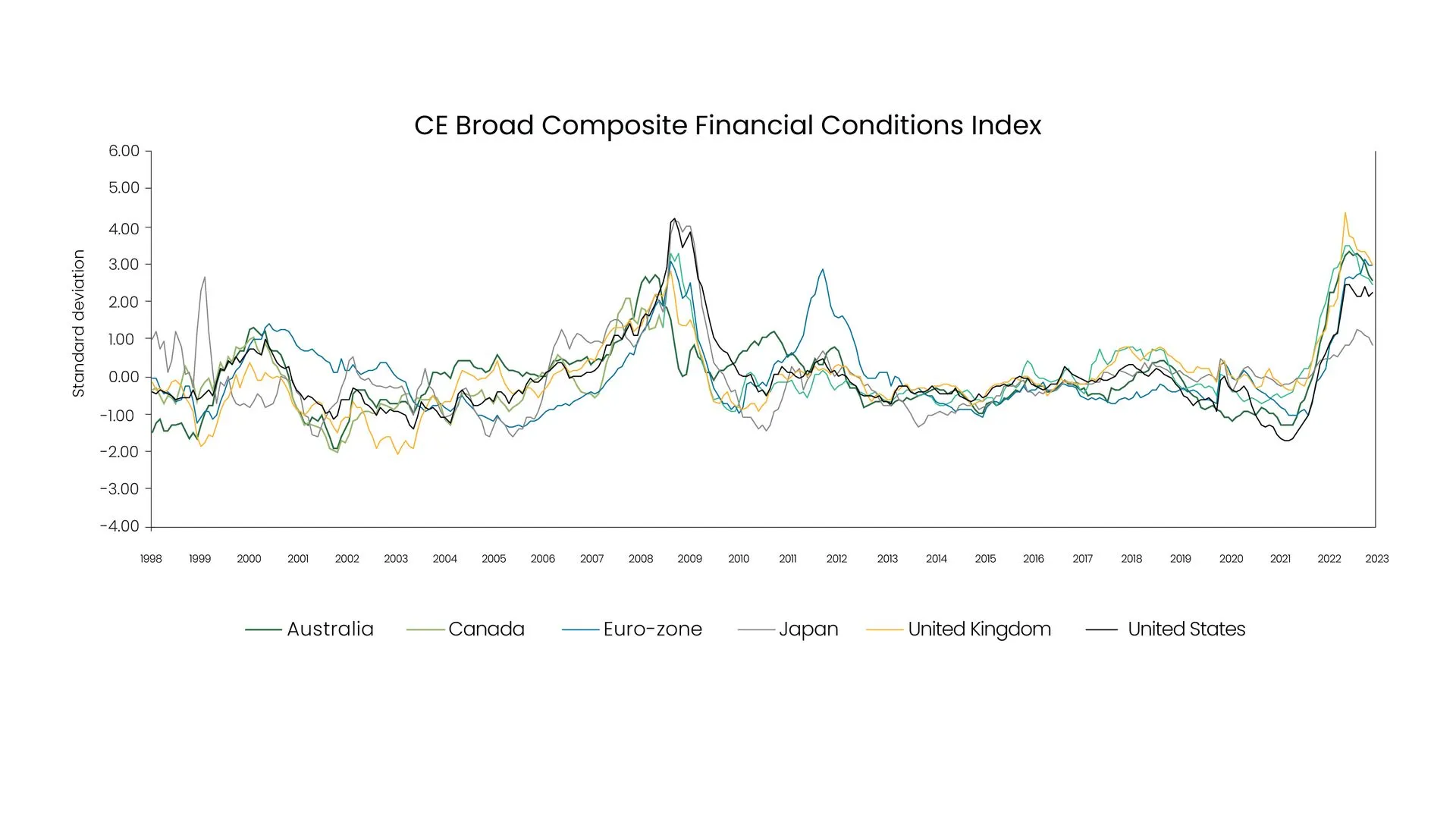

We still expect most major advanced economies to fall into recession this year. Financial conditions have tightened substantially across developed markets over the past 12 months, and history shows that this feeds through to the real economy with a lag (see Chart 1). Our analysis suggests less than half of the effects of monetary tightening so far have been felt in the real economy. In every cycle there comes a point where the economy appears immune to the effects of tighter policy, only for growth to roll over and recession becomes a reality. Nobel Memorial Prize laureate Milton Friedman said it well when he pointed out that monetary policy works with long and variable lags.

"As tighter financial conditions bite, we expect most major advanced economies to slip into recession and wage and price pressures to ease."

Chart 1:

Source: Capital Economics

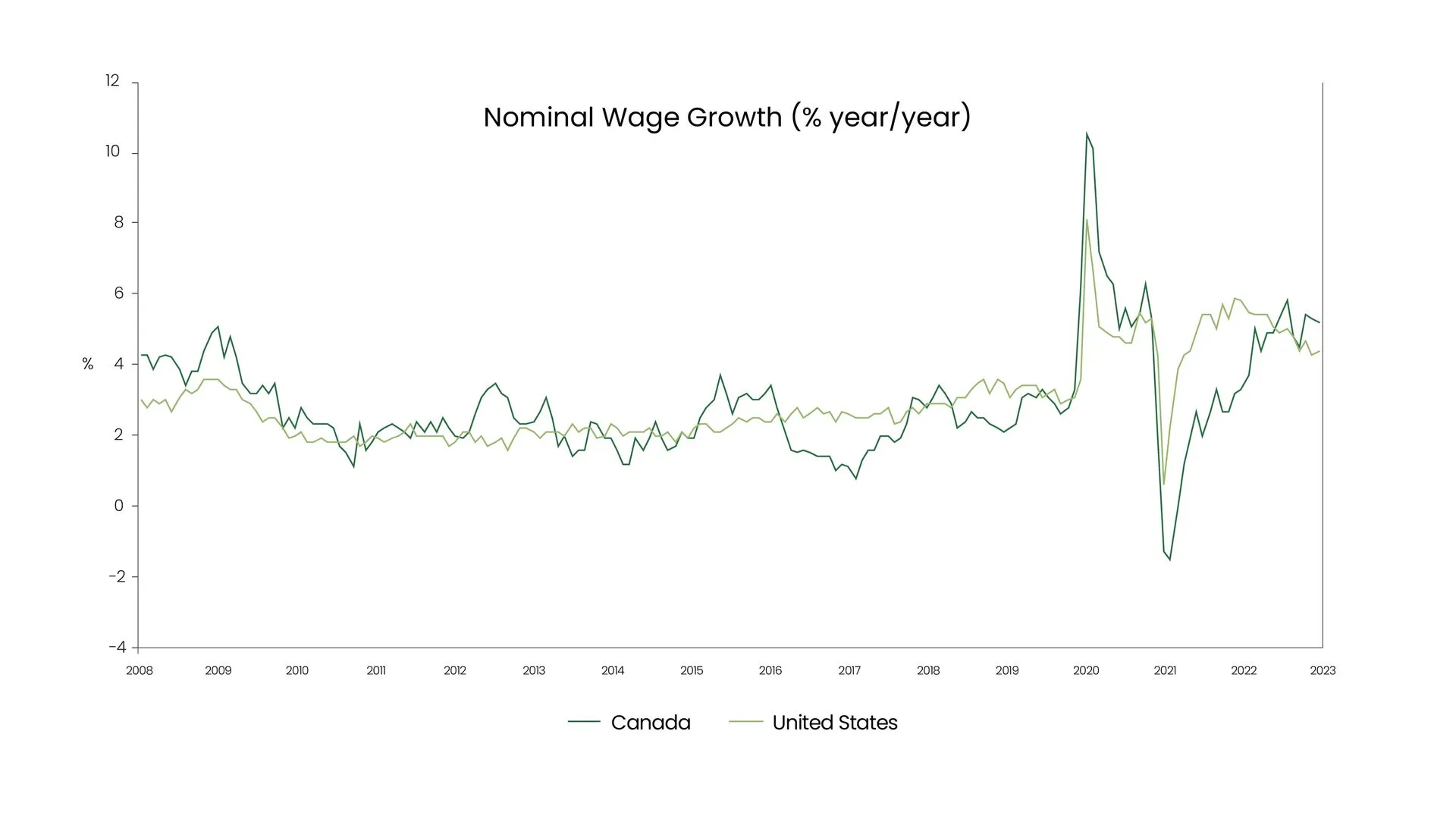

As tighter financial conditions bite, we expect most major advanced economies to slip into recession and wage and price pressures to ease. Leading indicators are already pointing to a slowdown in wage growth in Canada and the U.S. (see chart 2). In turn, that means it’s too soon to rule out interest rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve this year, although rate cuts in the U.K. and euro-zone are unlikely until 2024. With all that said, the recession we are forecasting should be relatively mild.

Chart 2:

Source: Capital Economics

What could go wrong?

There are two main risks to this view.

- Household savings accumulated during the pandemic means consumer spending remains resilient in the face of tighter policy, or that inflation doesn’t respond to weakening demand. Old models of inflation have broken down in recent years, meaning that it is extremely difficult to judge the response of wages and prices to changes in demand and to calibrate policy accordingly. It’s possible that central banks may ultimately have to tighten further to get inflation under control.

- The second risk again relates to how successfully central banks manage policy to meet their goals. The latest Senior Loan Officers Survey in the U.S. provides some reassurance that credit conditions haven’t dramatically tightened so far because of bank failures, although they do remain extremely tight. Comparisons that have been drawn between the current problems in U.S. regional banks and the global financial crisis in 2007-08 are misplaced, but as events continue to play out, it’s not difficult to see how this could translate into a further tightening of lending in the real economy.

Investors should draw two lessons from all of this. First, it’s extremely difficult to calibrate policy tightening at the top of most cycles, and pandemic-related distortions mean that it is particularly challenging at this point. Second, whichever way you cut it, the current calm in markets seems unlikely to persist. Either a recession will become a reality, which will knock down corporate earnings and equities, or inflation will prove stubbornly high, which will force central banks into additional policy tightening that is not being priced by financial markets. On balance, we think a recession is the more likely outcome.

"We remain cautious in our portfolios, taking a slightly more defensive posture given our above views and the strong returns for risk assets thus far in 2023."

Our Investment Views

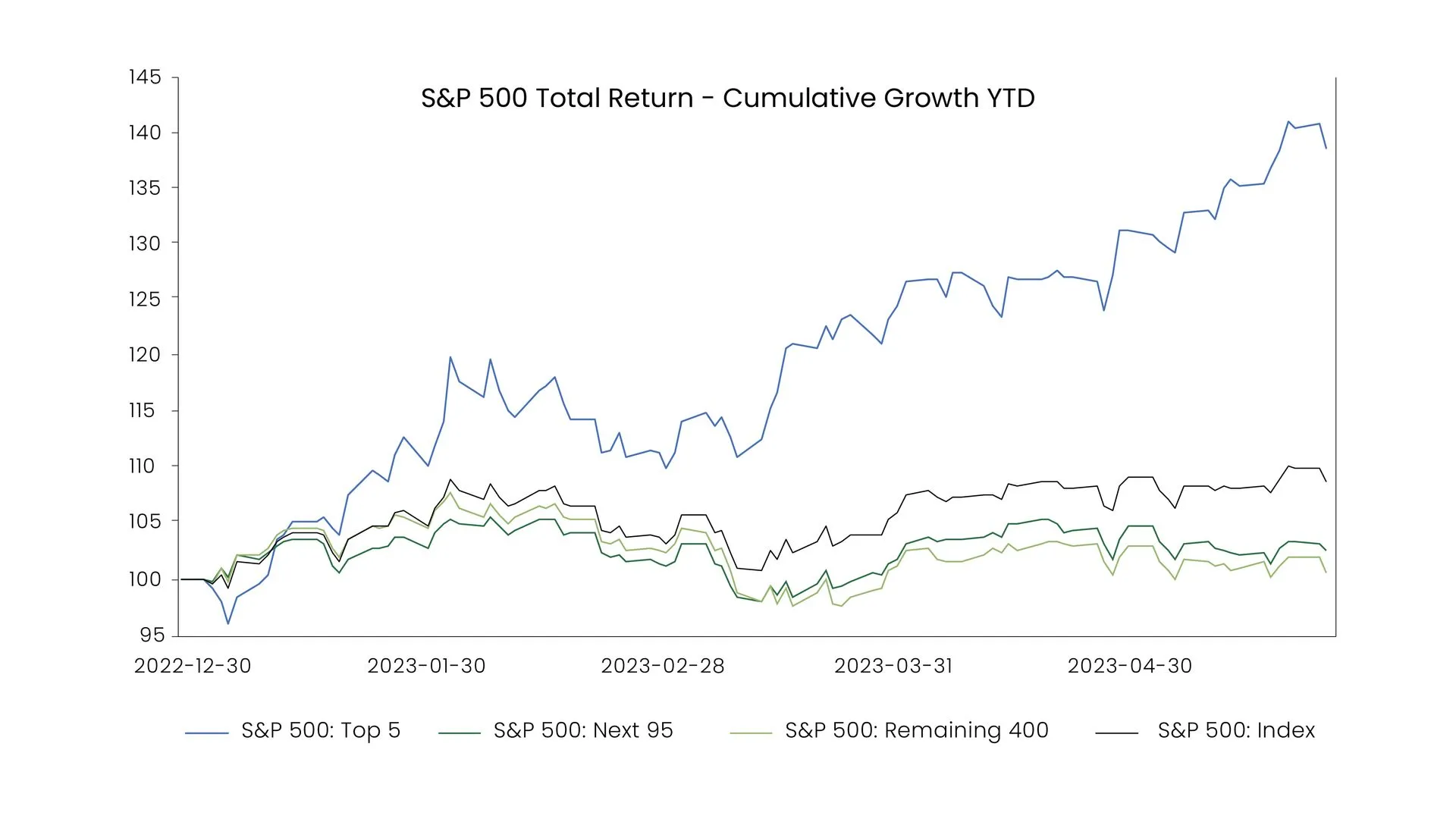

We remain cautious in our portfolios, taking a slightly more defensive posture given our above views and the strong returns for risk assets thus far in 2023. Most risk markets have posted solid gains in 2023 despite the financial turmoil that we have seen, but none more than U.S. equities. The S&P 500, as a proxy for large-cap U.S. equities, has posted a 8.7% return at the time of writing, but that has largely been due to a few “mega-cap” stocks. This is a trend that we doubt can continue for very much longer. A glance under the hood shows that this rally has been remarkably “thin” (see chart #3):

Chart #3:

Source: Morningstar Direct, Counsel Portfolio Management Team

It is not clear how much the rally in the mega-caps has been driven by optimism about recent breakthroughs in AI, lower bond yields, or a view among some investors about their resilience to a global downturn. But a portfolio of the largest five stocks in the S&P 500 has returned ~39% since end-2022. That accounts for ~80% of the S&P 500’s overall gains, with fairly meager returns from the other stocks in the index. (See Chart 3.) By our reckoning, ~70% of the S&P 500’s constituents have risen in price by less than the index this year while ~48% have fallen in price and ~21% have dropped by more than 10%.

While a “narrowing” in the U.S. stock market has not always been a signal that a rally in equities is about to come to an end, we still think that it could foreshadow a poor outlook for U.S. equities over the rest of this year. That largely reflects a view that a recession in much of the developed world has been delayed rather than averted and that growth will falter in the coming months. We believe that most other “risk” assets will deliver fairly poor returns over that period too, though the returns from “safe” assets could be much better.

As a result, we have increased our exposure to core Canadian fixed income across all of our portfolios, and reduced exposure to small-cap and global real estate. In addition, we have changed the composition of our U.S. equity exposure, reduced value equities, and taken advantage of the strong growth equity rally to also pare back our growth equity exposure and increase our multi-factor strategy, which we believe will be more resilient. Lastly, given our view that a recession will be relatively mild, the quality of the high-yield credit market, the attractive yields, and what we believe is a prudent trimming of our global bond exposure given the mandates strong year-to-date performance, we have increased our high yield bond exposure. We prefer high-yield bonds over global fixed income, focusing on core credit exposure and collecting attractive yields while having less exposure to emerging market macro risks. The early year risk-on rally in emerging market debt has generally played itself out, and at this juncture, we think it is prudent to take risks off the table.

Sincerely,

Corrado Tiralongo

Chief Investment Officer

IPC Portfolio Services